|

| Flowers and Confederate Graves at Riverside Cemetery |

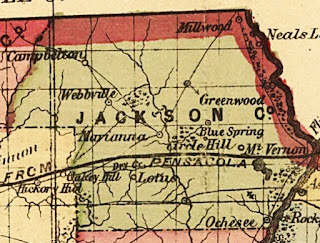

The trouble that took place at Marianna in May of 1867 is remembered today as the Battle of the Flowers. It began when local freedmen held a memorial service at the grave of Lieutenant Isaac Adams of the Second Maine Cavalry.

|

| Lt. Isaac Adams, 2nd Maine Cavalry |

|

| Scene of Heavy Fighting |

The women and children of Marianna were left to fend for themselves. Food ran short and hunger was rampant. Two homes, a church and the town's pharmacy were burned to the ground. The Union raiders carried away all the livestock and food they could get their hands on.

In short, the Battle of Marianna caused enormous suffering in the city and the people were left extremely bitter over the treatment they had received.

|

| J.H. Brett, Killed in the Battle of Marianna |

The day of memory was repeated on April 26, 1867, with the ladies of Marianna wearing their mourning attire and placing flowers on the graves of the Southern dead at Riverside and St. Luke's.

|

| Grave of Lt. Isaac Adams |

Although one recent writer describes them as "some young white women," all three of the girls were under the age of 16. One had lost a brother in the Battle of Marianna and another had seen a close friend shot down in front of her home. Right or wrong, they were insulted by the sight of the flowers on Adams' grave and removed them.

The action was not illegal, of course, and did not involve any desecration of the grave itself, but it quickly drew the attention of Bureau agent Charles M. Hamilton. He had suggested that the freed people place flowers on the lieutenant's grave and was outraged that three local girls had seen fit to remove them. It was the first real test of his almost unlimited power over the people of Jackson County.

|

| Charles M. Hamilton |

Instead of holding a military trial for three trembling young girls, Hamilton suddenly found himself faced not only by the girls, but by their attorney and a group of family members and supporters from the community. The Marianna Courier described the confrontation:

...An investigation was had, in which no reliable evidence was introduced to support the charge, and the young ladies were immediately released from arrest. We would advise our young ladies for the present, at least, to keep out of the way of these "Union soldiers" dead or alive. As there are no headboards, stones, or cenotaphs in the cemetery to guide your steps, it would be better not to go at all, for fear of treading unawares where you hadn't ought to, to spread flowers, or pick one up to decorate, for it might be called another name and you be punished. - Marianna Courier, May 30, 1867.

The people of Marianna reasonably believed that Hamilton would have punished the girls had their family and friends not turned out in force to support them. They also considered the agent's attempt to try three teenagers before a military court to be egregious abuse of power and reacted accordingly. News of the incident spread and the "Battle of the Flowers" became the rallying point around which organized resistance of the occupiers began to grow.

Frank Baltzell, the local newspaper editor, had been captured in the Battle of Marianna and had seen his friends Littleton Myrick and Woody Nickels burned at St. Luke's Church. He used the power of his press to heap scorn on Charles M. Hamilton:

|

| "The Sacred Spot" |

Our town authorities should immediately provide another avenue to the burial place of our dead that the "Sacred Spot" be not viewed much less approached, at the peril to the innocent and unsuspecting. - Marianna Courier, May 30, 1867.

In the view of Marianna's former Confederates, the gauntlet had been thrown down by Hamilton and they now prepared to resist him in his further actions. In carrying out a military trial of three teenage girls, the Bureau agent himself ignited opposition in Jackson County. The Reconstruction War had begun.

I will continue to write about the Reconstruction War in Jackson County over coming weeks, so be sure to check back often. To read previous articles on this topic, please visit the main page at http://twoegg.blogspot.com.